2003_11_21

Marian's Drawn Memories

(1-8)

I deem it important,

to add the scanned German version

WORDS THAT ARE DRAWN, WORDS THAT

ARE SPOKEN

By Marian Kolodziej

[See also the

photos, taken by our Polish participant Ola, on her website :

www.elenai.art.pl/oswiecim.html ]

1

This is not an exhibition,

This is not art.

These are not pictures.

These are words locked in a drawing

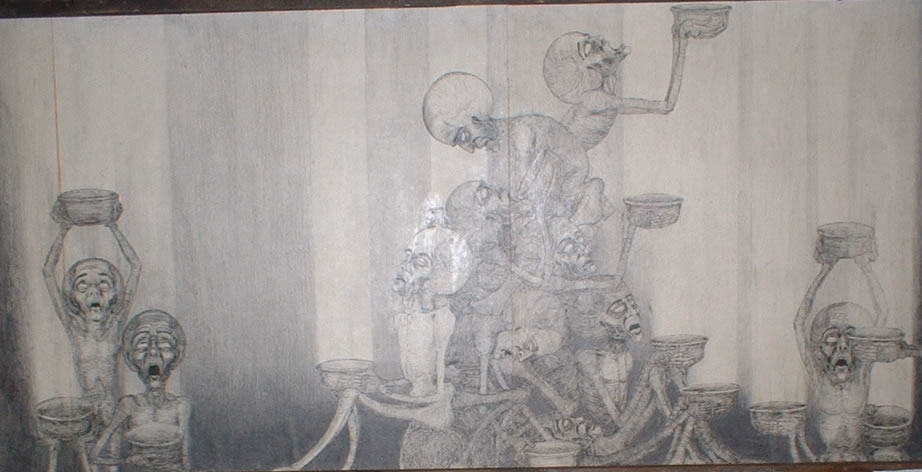

Christmas and Passah:

Pater Stanislav and I watched this composition for a very long time

and understood:

It is not the celebration of the birth of God's Son,

but The Last Supper of twelve alive sceletons who mourn his transfigured

sacrificed flesh and blood.

2

I was in Auschwitz.

I built Auschwitz

because I arrived there in the first transport.

It is also true that for almost fifty years I did not speak about

Auschwitz.

But nevertheless throughout that whole time,

Auschwitz was present in everything I did.

Not literally.

One can understand my work for the theatre as a protest against what

I experienced there.

Although I usually tried to be faithful to the text and to the stage

directions,

I would often smash apart the space on the stage.

I even think that it was not only a matter of smashing apart and opening

up that physical space

which there, in the camp, was closed.

I was always very concerned to have interior space show some other,

further interior.

I looked for this in the people who entered the stage,

and not in the place where they were, in a room or on the road.

My designs were compositions.

The camp was chaos, disorder.

In the theatre I made sure that the physical organization of the stage

actually meant something.

These were always shattered structures – spaces, cosmos, light.

In my work, I always attached great importance to light.

The multiplicity of details in my stage designs had concrete meaning.

Forms which receive the light,

reflect it

and return it to other forms.

And this gives the impression of luminosity, of air.

Just like by the canals of Venice -

the reflections of the houses rebound on the houses or the bridges,

and all Venice is light itself.

So Auschwitz was a constant presence – but as

its own denial.

I did not trust literalness.

One cannot speak of the camp in literal terms.

I always tried through my experiences to look for common ground with

the audience

by means of signs

which are known to all of us,

which we share -

broader and deeper than those which are only the external props of

martyrdom.

For me they were something shameful –

Those mannequins in concentration camp pyjamas,

seemingly dead, beaten, tortured on the stage,

Those gestures of despair,

Those sad faces,

Those polystyrene jackboots,

those taped SS shouts -

that entire instead of,

that entire superficial half-truth.

For the camp is not just beating,

not just death from work beyond human endurance,

not just a slow physical death,

constant hunger,

lice.

It is also a silent, interior NO,

a rebellion within the limits set,

an endurance to spite them all.

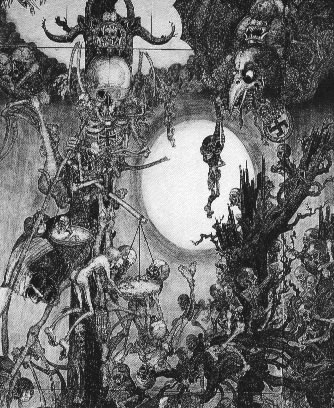

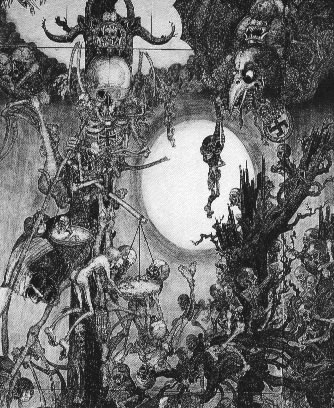

Only once in my stage designs did I refer directly

to the camp, but the text demanded it.

It was Sito's "The Damnation of Doctor Faust".

But I did not try to create the camp on the stage.

This was where I quoted Duerer's "Apocalypse",

but I didn't do that literally either.

I projected the "Apocalypse" onto the audience's backs,

onto their heads.

From the back rows you could see the whole of Duerer's vision,

with contemporary people inscribed into it.

3

I do not know if I would have ever gone back to Auschwitz,

if it hadn't been for my illness.

My drawings stem from my illness.

Drawing became a battle for life.

I wanted to get away from the illness, even if only for a little.

At my age, you never really recover your health.

In other words, there was no great plan, just an attempt to save myself.

Afterwards feelings of duty came into play.

There was a chance to do what I had promised my friends when we were

in the camp,

my friends who died

and who – like Stefan Jaracz – imposed the duty on me

of acquainting people with what had gone on there.

But if I had felt fine, if I hadn't fallen ill, would I have gone

back to the camp at all?

The whole thing came as a surprise.

I got out of hospital and at home I began to do exercises.

The hand, the fingers, the legs.

Drawing was the best exercise of all.

In the camp, I was involved in the resistance.

So I had a purpose – the struggle.

And I thought that it would stay that way.

But the drawings began to muliply fast.

For me that was incredibly important.

I copied plans of the camp

and the factories which had been transferred here from beyond the

Rhine.

I had to survive to do it.

Now it was the same in this illness.

I began to draw to survive.

The aesthetically sophisticated stroke which everyone pursues was

quite beyond me.

I had only a block of technical drawing paper.

32.5 by 23 centimeters.

So I was drawing on little sheets of paper,

In the beginning there were only a few of them,

But then they started to increase in numbers more and more.

I don't know why myself.

Maybe the increase drew strength from that mixture of feelings I had:

My fighting for my own life,

And that sense of duty aroused after all those years.

So, first of all, there was my illness,

Then the memory of the camp, And then I really don't know what.

Because I stopped being in control of what happened afterwards~

Of my own free will, I shut myself up in the camp once more.

This time for a year.

4

My drawings are meant to replace photographs.

Since there was no photographer in Auschwitz,

in my drawings I really tried – often against my own impulses

– to get near to photography,

without making them too literal.

But I tried to make them expressive enough

so that the viewer could also feel what was going on

inside me.

In my drawings there is no martyrdom –

There is only the posing of a problem.

I had a general plan only in my head.

I couldn't put it all on paper as a whole picture.

That's why I made photographs of details

which later found their place in the revised composition.

I carried the composition inside myself.

And that's where the threading together of details comes from.

But they have their own points of reference.

I don't invent anything;

I only borrow, quote, hold a conversation with the history of art.

I hold a conversation with Duerer, with Memling.

I take certain postures from them -

to express suffering, pain, despair -

and place them within twentieth-century experiences.

It is important for me that what I draw to be understood today.

Those postures or gestures of theirs are very theatrical,

but that's the very thing that seems to me to make them familiar.

For years I encountered them every day in the theatre.

So I did not propose a new way of expressing despair;

I only used what I had seen in museums,

what I had observed in works of art.

A great deal had already been experienced and presented by artists.

It was difficult to compete with all that – especially given

my paralysis.

I first began to learn the centuries-old language

through which I could express my suffering right after leaving the

camp, in Austria.

The first days, weeks of gulping down draughts of freedom

were also a time of swalling huge draughts of art in the galleries

and museums.

It was the Gothic above all that moved me.

I took over what was the expression of suffering in the Gothic.

The Renaissance and later the Baroque created more theatrical gestures.

In any case, they were agreed on signs – sign-symbols.

The gestures of the Way of the Cross are everywhere the same.

I thought about making references to contemporary art.

It would probably have been quite easy for me to find some contemporary

form,

even an abstract one,

which would have expressed my experiences.

I could have found it in only one patch of colour.

But that would have conflicted with what I intended to do.

A contemporary form would not have allowed me to fulfil

the duty I had

"to photograph memory".

I tried to create abstract forms,

but they had no power of expression,

they said nothing.

That is why at a certain moment I decided that my drawing would be

a word,

that I would enclose all my experience in the line of the pen.

So I did not look for new means of expressing suffering.

I did not play with form; I did not sit back and relish form.

I realized that such an aestheticization was not suitable in the face

of last things,

that it was necessary to speak in a language which

people knew already,

with which they were familiar.

After all, I wanted to speak to them,

and since that was the case ~~~

So I began to look for a sign which would not only be a human being,

but also an animal and a fly~~~

And which would not at the same time lose its individuality.

It did not seem fitting only to give the outline of a figure, only

to feign its appearance.

Out of respect for those who had been with me in the

camp,

I tried hard to reproduce those remembered faces as faithfully as

possible.

Like a photographer.

5

While drawing,

I returned to the experiences of a teenage boy

Growing up among thousands of men,

Placed in extreme situations,

In a world in which everything could happen,

In which people's reactions were unexpected –

Here one person curses his own death,

And there Kolbe goes to his death in place of another.

Polar opposites.

I remember a violinist, an old Jew

Who tried to give me a shovel begging that I finish him off with it;

he didn't want to live any longer.

That's the way it was.

And I came into the camp completely inexperienced,

with my boy-scout ideas that had been instilled into me along with

my patriotic upbringing.

I tried to protect myself somehow.

I did what I could.

I certainly do not want to be wiser in my drawings than I was then.

I tried to return to my youthful naivete

Now, as an old man, I write a letter to myself from years ago,

and I try in my drawings to put in order and preserve only what survived

with me.

Only what I managed to save and what is now in me.

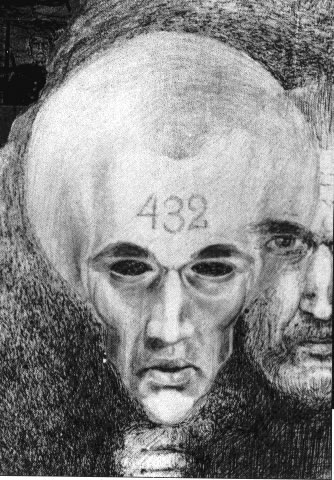

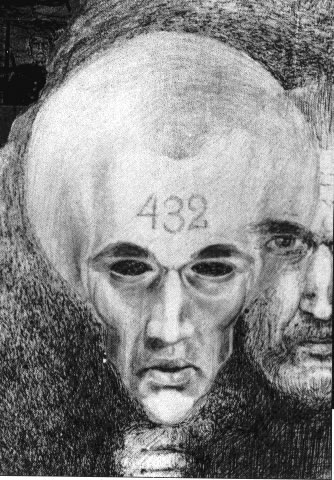

In one of the drawings I juxtapose myself as I was fifty-five years ago

and myself as I am now.

one of the drawings I juxtapose myself as I was fifty-five years ago

and myself as I am now.

It is a kind of double self-portrait.

But the face of the other, from the camp, is a mask.

The real face is the one from now.

In the camp, life was pretence,

hiding oneself behind something.

In the picture, I uncover myself.

In it I place what for me is the most tragic thing of all.

One time before, in the stage design for Hindemith's "Matthew

the Painter", I used these motifs.

There is a black sun,

Gruenewald's Christ as an expression of the highest degree of suffering,

And an alarm clock which I dug out from the ruins of the crematorium.

It is time held still for five and a half years.

But will it have any meaning for anyone besides myself?

6

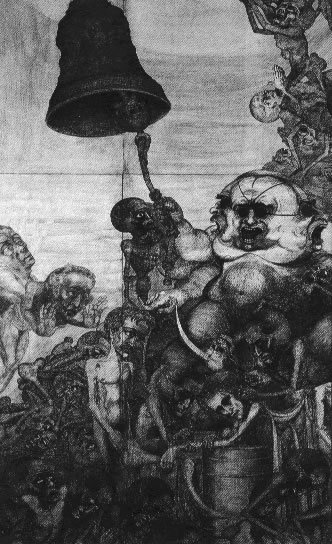

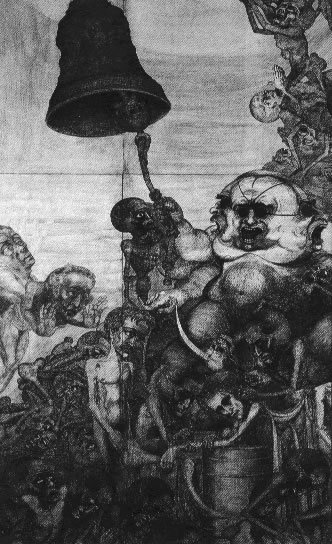

On the parade ground there was a bell.

And the bell is in my drawing too.

This bell summoned us everyday to muster;

but it rang too for the execution of hostages,

which we were all forced to witness.

You never knew if it was only the notification that it was time for

the daily count,

or if it was the announcement of a death.

Today I see in it a summons to the Last Judgement.

It was Krankenmann who rang the bell.

That was the name of the man who was for me the worst of all the Germans

in the camp,

A kapo – nomen omen -

"Sick Man" in German.

When the bell rang, we came out naked, stripped of our clothes and

our names,

Our heads shaved,

doused with lysol.

We are already just numbers,

And they bring us even lower after that.

This drawing is my conversation with Memling,

a questioning of his belief in a just judgement of life.

I draw only hell.

Heaven is not present.

The matter is one only between human beings.

There is no external world either.

It has not been drawn.

And do they-we go down already condemned by the finger of providence?

Into their-our own abyss.

7

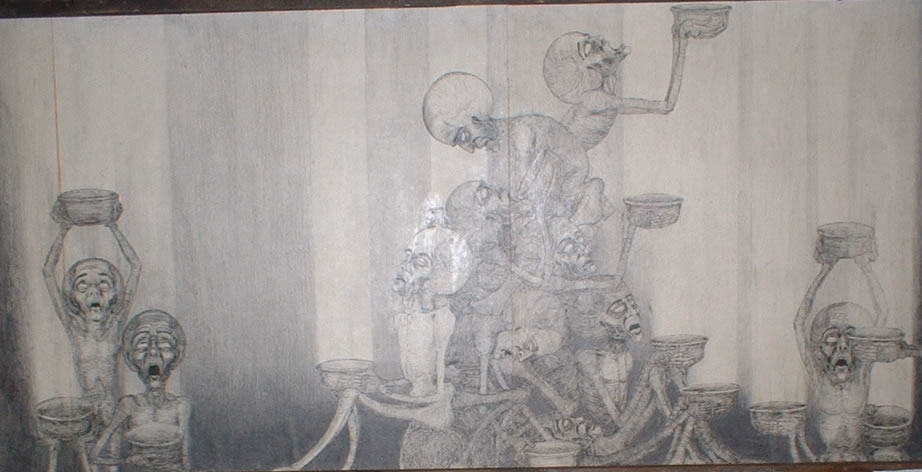

The loaf of camp bread, always the same shape, was

supposed to be cut into four pieces,

One for each prisoner.

It was never that way.

We never got more than one slice.

All the rest vanished on the way to us.

Many hands grabbed their share as the bread ration was distributed

to us.

The kitchen kapo and company,

The barrack boss with his court,

The room supervisor and his pals

- only at the end, we, the prisoners, with our primitive scales made

out of a stick.

We weighed those slices, and then we divided up the crumbs of bread

So that everything was equal.

That was our internal justice.

On the other hand, what went on outside, around me

in the camp called into question my whole upbringing,

the boy-scout patriotism which I had carrid away from school.

Although at the same time that upbringing was useful to me.

It was that upbringing which brought me unsullied through the camp.

I don't know what would have become of me without that

upbringing -

what kind of scoundrel I would have become.

I don't know what would have happened to me.

Going back in my drawings to those times,

I tried to revive and maintain my old naivete.

For then I only spoke the language of good and evil.

As I had been taught, I would weigh

up good and evil.

The angel guides the child over the footbridge.

I saw things that way, in that sugar-sweet way,

just like in the picture in the sacristy or in the

Catholic Guide.

Often people, trying to explain how Auschwitz was possible,

forget about that constant tension between good and

evil.

To have your own scales!

To have your own scales!

Such a scales as we had in the camp when we weighed

the bread which had been weighed once already.

And the crumbs which we break off from one person's

ration,

we give to the other.

We weigh two little lumps.

Things are in order with us.

I am not speaking only of bread.

For me it's not just a matter of bread.

People who are in an extreme situation -

Kepinski wrote about this many times -

have a sharpened sense of justice.

Different from the one which applies when you are free.

This difference was very clear when in 1941, in June,

July and August, the first transports arrived from Warsaw.

The people on them came from round-ups in the street,

but from freedom - so they were well-fed.

After our experiences in prison we were full of solidarity

with each other.

But they weren't.

Out of our daily ration -

made up of soup and a little lump of bread -

we would keep aside the bread for the morning

so that we could get through the day.

After the Warsaw transports arrived, we woke up - and

there was nothing left.

They robbed us of everything.

That was the end of solidarity.

And it was the beginning of dealing, thieving, crookedness~~~

Cannibalism

Nowadays everybody speaks about values;

they overuse the word.

But after all, everyone has their own privat values,

filtered through their own experience.

They are there and have to be there.

8

One day we had a German lesson,

but it was really a lesson in following orders and

reporting.

The bored officer,

seeing that his lesson wasn't getting through to us

very well,

ordered us - as a punishment - to climb a tree,

and as we climbed we had to shout out correctly a hundred times the

way of reporting he had taught us:

'Number 432 meldet sich gehorsam!" (Number 432 is reporting obidiently!).

Along with dozens of shrieking companions I clambered

as high as I could

to get away from the frantic, snapping dogs below us.

Behind me the cracking of breaking branches,

the wild howling of the Alsatians,

the laughter of the amused soldiery and kapos,

the wailing of those who were falling.

But despite everything I manage to get up high,

and I suddenly see beyond the electric barbed wire

and beyond the concrete wall that shuts us in,

people from outside who are going somewhere in carts,

who are hurrying somewhere, going about their business.

If I fall,

I could lose my life,

and in any case I will be going back to a situation

in which death threatens every minute.

So this view of the world outside,

at last a view of these colourful little farmsteads,

surrounded by flowers and greenery

which remind me of my own family's,

this view, which I had been deprived of for months

because they'd put up a concrete wall in front of it

so that I couldn't see the life going on there

- this view is something unimaginably beautiful,

and I look at it greedily

so as not to lose any of it.

Then the fall is even more terrible.

It was the tree of life and death.

one of the drawings I juxtapose myself as I was fifty-five years ago

and myself as I am now.

one of the drawings I juxtapose myself as I was fifty-five years ago

and myself as I am now.