|

2003_11_21 Marian's Drawn Memories

(9-15)

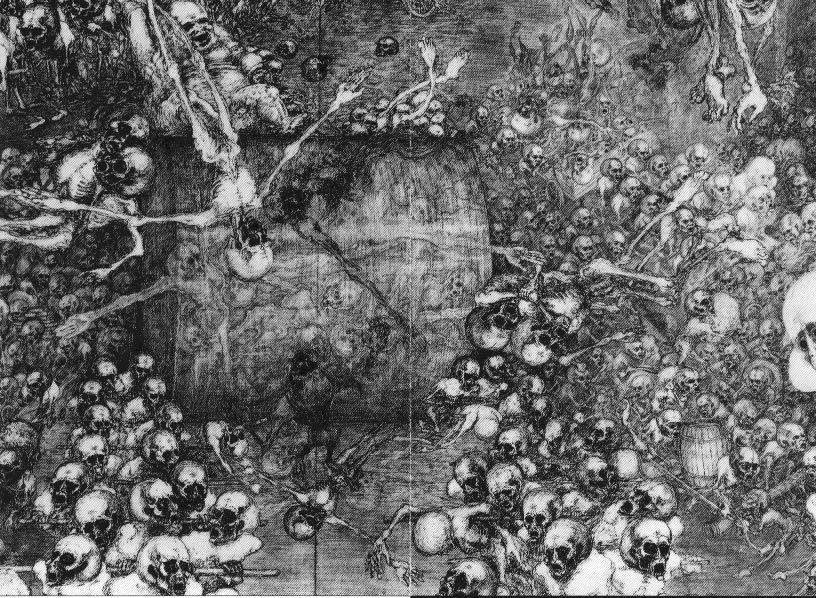

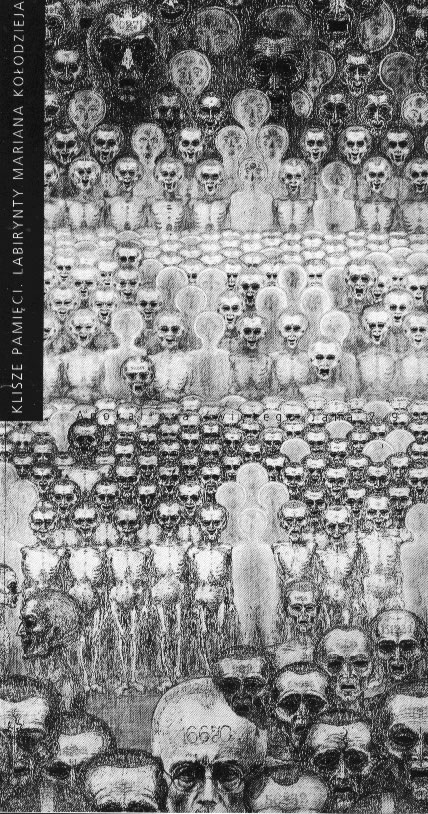

9 The apocalypse is a kind of dream. It is a picture that a teen-age boy saw in a dream, remembering Duerer from reproductions hanging in his school corridor. During the first years we slept on the ground crammed together in an unimaginable fashion, squeezed close. The whole room on its left side because that's the way the first man lay down. If the first man lay down on his right side, then everyone had to lie on his right side. The head of the man in the second row on your knees, and in that way you got five hundred sleeping in one stinking room. By the door, a latrine barrel filled to the brim with urine and excrement. And I'm there too. I sleep and see the massed attack of the many-headed Beast, of horses, of dragons and of reptiles - it is the whole cruelty of the day united with the loathesomeness of the night, it is the kapos, criminals, degenerate murderers, executioners, sadists, it is the everyday life of the camp. It is like in the Bible. The Four Horsemen, the Whore of Babylon, plagues from the sky. Everything According to the verses of the Apocalypse of St. John, but all crammed into the camp, into the reality of the camp. We made this Apocalypse in ourselves, for ourselves.

And today I dream in the same way and I dream the same things. In these dreams the Beasts come back, repugnant, brutal, predator, cruel - people. One of the Horsemen of the Apocalypse has in his hand the same scales from the camp, the one made from a stick.

I would like to prompt the viewer: be patient, patiently read everything that is recorded in these pictures. These are my "words that are drawn" for you. You have to read them. Through the smoke from the crematorium that I will dream about for all eternity, I do not see the sky. Sometimes there is only a cry. Someone is running through the camp and calls aout, "Where are you, God?"

10 The camp gate - on it at the top the sign "Arbeit macht frei" with its lying promise of freedom through work. For hundreds of thousands it was only a way in. The way out of the camp into freedom was to be only through the chimney. Auschwitz was a camp of destruction; you were worth something there if you were still able to work. You had to be able to do any kind of work - then you had some kind of chance - for a time. Lagerfuehrer Fritsch promised you three months. But there were periods when the Third Reich, threatened on various fronts, needed your hands, your skills. Then you would more frequently pass through that gate.

The orchestra played cheery marches, the finest band composed of the most outstanding musicians of Europe. You marched in step, erect, smiling, in drill formation - to build factories, roads, canals, to unload wagons, to do work beyond your strength "im Laufschritt" - at a run.

The return from work, those beaten, tired columns, bleeding and dead, ought to have beeen Accompanied by a funeral march.

11 Krankenmann - the monstrous Beast on a huge roller. There and back, there and back - at a run the whole working day. Twenty pushing, twenty pulling. About tuirn and return. Anyone who, weakened, falls down, stays, crushed, on the ground. We are smoothing out the future muster yard.

All the while, life in the camp goes on normally. Someone brings a barrel with food. People eat, relieve themselves, die.

12 Outside the block, on the wide muster yard, some prisoners stood constantly, already completely passive, apathetic, utterly emaciated, hounded to death, frozen to the bone, hungry. In groups - the Muselmen. The whole day, listless, they simply stood there.

The musters always terrified us. Supposedly they were only a way of checking the number of people in the camp. Someone had always gone missing, had crawled off into a corner to die, or, God forbid, escaped. We stood during theses hated musters for hours, for nights, for days. In torrential rain, in mud, in snow, in frost, in scorching heat. The ones who were still healthy, the sick, the dead. Utterly worn out by "sport", at attention, squatting, beaten, decimated.

Three such nightmare "stands" stick in my memory. A prisoner called Wiejowski had escaped It was the first escape from the camp. We stood through the evening hours, a cold night, day break, morning, in the baking heat - one o'clock, two, three, four Around six I crawled back to my block. I had to tear open my camp uniform, my body was so swollen.

The second muster was a selection. Ten for one with the immortal decision of prisoner number 16670 - the decision to give his life for an unknown fellow-prisoner, in the evening of the last days of July. That was Father Maksymilian Maria Kolbe - on 14 August 1941 at 12.50, as the last one left alive, he was finished off by the executioner Bock with an injection of phenol in the starvation cell of Block 11.

I was at that muster.

I called the third tragic muster the dance of death. It was not a stand, but a never-ending run by a crowd of nine thousand prisoners round the muster yard. Rain mixed with snow was falling; a strong wind was blowing. Anyone who weakened and fell was crushed into the mud, trampled by thousands of wooden clogs.

13 In this daily wearing down of your self-respect in this despairing desire to save some kind of moral standards, an unexpected miracle occurred. Meetings with the actors Stefan Jaracz, Tadeusz Kanski, Zbyszko Sawan, and with the director Leon Schiller were secret. They took place on Sunday afternoons, during the two hours of free time immediately after delousing. "To refresh the heart" they recited Mickiewicz, Slowacki, Krasinski, Norwid, Wyspianski. We were deeply moved as we listened. In such extreme conditions - anus mundi - those most perfectly spoken Polish words were a reviving bath cleaning us of the vile dirt of the camp's slang.

In the degenerate life of the camp we were not only beaten with whips, but they did it too with the brutal, vile, coarse word, the most monstrous of curses. Two solemn hours of the purest experiences, at last in a Poland so beautifuly conjured up in Jaracz's inspired, brilliant interpretation.

My role as a stage designer boiled down to covering the windows with blankets so that all was safe and quiet. The performances of the greats of our theatre and my tiny contribution towards organizing them showed me my future profession.

It was they who infected me with it, and gave me the duty to remember, not to forget what was human in me and what had been saved with such terrible difficulty.

14 In the death cell, untying the knotted ropes, I am not alone. With me is my sorrowing shadow.

15 The last day: the loading-platform, the gas, the crematorium. Mene, Tekel, Peres - numbered, weighed, divided. I would not dare to say which is more terrible - the tragedy of a prisoner dying through five long years or that of a man dying suddenly in unconsciousness - right away. I cannot permit myself even to think of weighing up this dilemma.

16 After the chaotic evacuation of Auschwitz at the end

of 1944 a sequence of camps: And surprised by the grace of God, of Providence, of

Fate, I weighed 36 kilos. On my left hand will remain forever the tattooed number 432/

17 Today, from the perspective of the years, I am absolutely certain that, it is because of those experiences in the camp, because of the hell that I went through. I learned and I taught myself to live - in isolation and in the herd and for the herd. To live honestly and worthily, to have a conscience. Maybe it was worth going through all that?

Looking in advance from my life's close at this twentieth century

of ours which is coming to an end,

I see that after Aushwitz not only did nothing change on earth - though it was supposed to - but it is worse. The laws of the camp still govern the world. The monstrous Apocalypse from my drawings endures.

" Night of People"

- Yael, my granddaughter, age seven, 2003_11_22

|