|

InteGRATion into

GRATeFULLness

Singing&Sounding keeps me Sound

Da neigt sich die Stunde und rührt mich an

Ich lebe mein Leben in wachsenden Ringen

| 2007_03_30 Da neigt sich die Stunde + Ich lebe mein Leben in wachsenden Ringen |

lyrics:

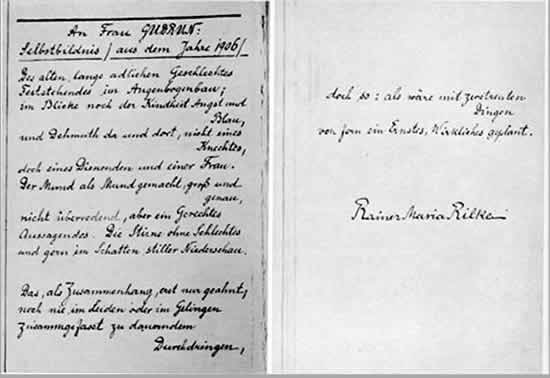

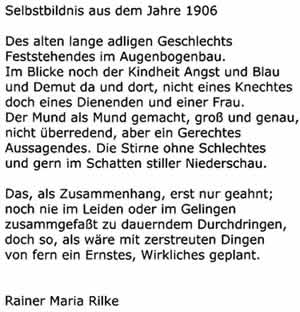

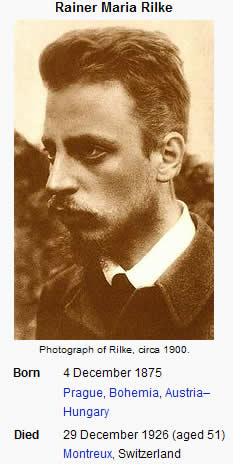

Rainer Maria Rilke |

tune: Christa-Rachel Bat-Adam Arad, Summer 2005 |

According

to a website also somebody else composed a tune to this poem in German but I didn't find a translation |

Da neigt sich die Stunde

und rührt mich an

mit klarem, metallenem Schlag:

mir zittern die Sinne. Ich fühle: ich kann -

und ich fasse den plastischen Tag.

Nichts war noch vollendet, eh ich es erschaut,

ein jedes Werden stand still.

Meine Blicke sind reif, und wie eine Braut

kommt jedem das Ding, das er will.

Nichts ist mir zu klein, und ich lieb es

trotzdem

und mal' es auf Goldgrund und groß

und halte es hoch, und ich weiß nicht wem

löst es die Seele los...

An attempt to translate the

last stanza for "Firing the Grid":

Nothing is too small for me, and I

still love it,

and paint it on gold and huge

and lift it high up, and I don't know whom

will it untie the soul.

From K.i.s.s.-log 2008, August 28

|

Song of the Day

[the tune came to me, when

I

came across the translation of one of the poems by Rainer

Maria Rilke which I knew by heart]

The

next day I came across another translation, by chance: I'm circling around God, around the ancient tower, |

See 3 more poems - one of them - In diesem Dorfe - was put to music by me - which were translated by the same author

|

![]()

On March 19, 2010

I decided to copy as much of my clippings from Rilke's

Letters as possible,

They inspire the understanding of myself and my experiencing the World.

And mainly - they teach me to move from

"feeling-experiences

towards the desire to feel everything feelable".

It is from feeling, moving, accepting every feeling in every moment,

that I draw joy, even ecstasis about the smallest and biggest "things"

[see the present closure - March 27

- of the Song Page: "Desert

Earth"]

From an

"Index" of Rilke's Letters: "Von Rilkes

Briefen sind bis heute ungefähr 7000 veröffentlicht worden....

Der Dichter geht feinfühlig auf seine Briefpartner ein, nutzt die Korrespondenzen

aber auch zur Selbstreflexion."

I cannot understand, how Rilke, the ultimate "FEELER", let himself

die at the age of 51

The paper-slips, which I've kept for many years, are in a turmoil, and not

always dated,

but what I find relevant for me up to this day, shall be inserted in a chronological

way.

The background is a mystical reflection of

Mika in the car to kindergarden this morning.

[~~~ means: omissions by the editors of

the Letters; ... means : omissions by me]

|

For too many days now I have not written of the sea, Nor the rivers, nor the shifting currents We find between the islands For too many nights now I have not imagined the salmon Threading the dark streams of reflected stars, Nor have I dreamt of his longing Nor the lithe swing of his tail toward dawn I have not given myself to the depth to which he goes To the cargoes of crystal water, cold with salt, Nor the enormous plains of ocean swaying beneath the moon. I have not felt the lifted arms of the ocean Opening its white hands on the seashore, Nor the salted wind, whole and healthy Filling the chest with living air. I have not heard those waves Fallen out of heaven onto earth, Nor the tumult of sound and the satisfaction Of a thousand miles of ocean Giving up its strength on the sand. But now I have spoken of that great sea, the ocean of longing shifts through me, the blessed inner star of navigation moves in the dark sky above and I am ready like the young salmon to leave his river, blessed with hunger for a great journey on the

drawing tide.

|

|

|

2010_03_25-27

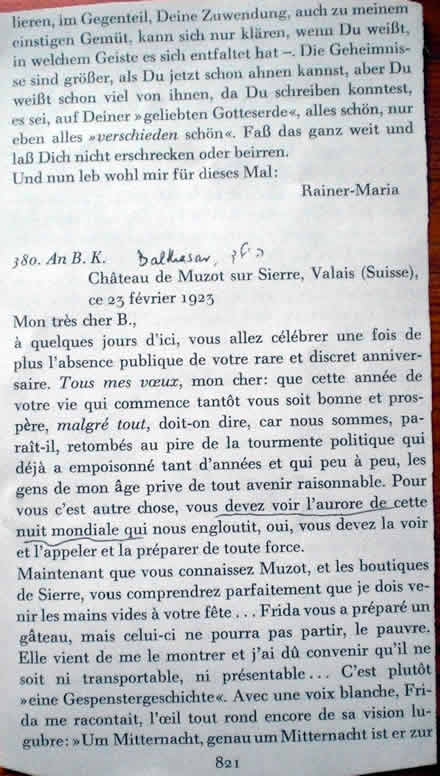

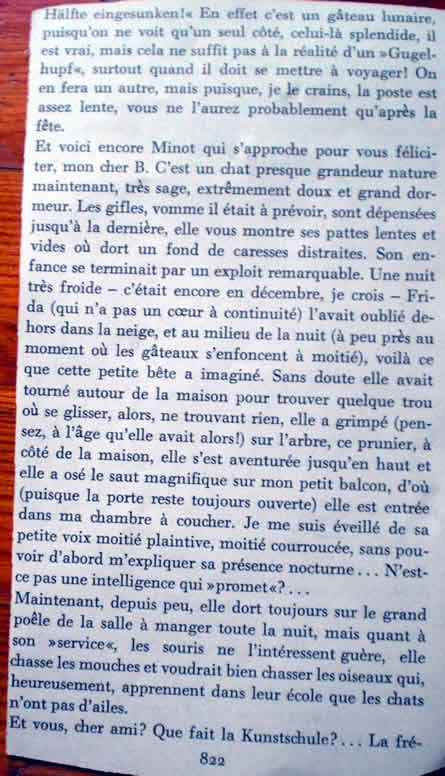

| Early 1923, to a baronesse,

whose mother had died? ...Mehr als einmal schon hab ich Ihnen angedeutet, wie ich mehr

und mehr in meinem Leben und in meiner Arbeit nur noch von dem Bestreben

gefuehrt bin, ueberall unsere alten Verdraengungen zu korrigieren,

die uns die Geheimnisse entrueckt und nach und nach entfrendet haben,

aus denen wir unendlich aus dem Vollen leben koennten. p.828

... Wer nicht der Fuerchterlichkeit des Lebens irgendwann, mit einem

endgueltigen Entschlusse, zustimmt, ja ihr zujubelt, der nimmt die

unsaeglichen Vollmaechte unseres Daseins nie in Besitz, der geht am

Rande hin, der wird, wenn einmal die Entscheidung faeelt, weder ein

Lebendiger noch ein Toter gewesen sein. Die Identitaet von

Furchtbarkeit und Seligkeit zu erweisen, dieser zwei Gesichter an

demselben goettlichen Haupte, ja dieses einen einzigen Gesichts,

das sich nur so oder so darstellt, je nach der Entfernung aus der,

oder der Verfassung, in der wir es wahrnehmen~~~:dies ist der wesentliche

Sinn und Begriff meiner beiden Buecher

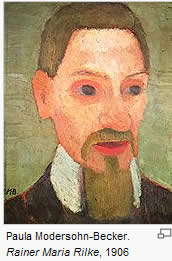

[Duineser Elegien und Sonette an Orpheus]... 1906, An Karl v.d. Heydt

[erster Maezen Rilke's, see info &

photo in an

essay about "Rilke's summer at Friedelhausen"]

|

From

36 Rilke- quotes in English While delighting in Rilke, And in the French Wikipedia it's

noted,

"Seitdem Rilkes 1902 das kleine Haus in Westerwede bei Bremen, wo ihre Tochter Ruth ihre erste Lebenszeit verbrachte, hatten aufgeben müssen, waren sie ohne festen Wohnsitz, auf Einladungen und Stipendien angewiesen, mit unsicheren Einkünften. Rilke war jetzt 29 Jahre alt, der Versuch, sich mit Zeitschriftenbeiträgen, Auftragsarbeiten, Rezensionen finanziell abzusichern, scheiterte, weil ihn das an seiner "eigentlichen Arbeit" hinderte. "Hier kam es auch

zur Begegnung mit Gräfin Luise von S c h w e r i

n : "Rilke war schon

1902/03 in Paris bei dem Bildhauer Auguste Rodin gewesen, über

den er eine Monographie verfasste - eine Auftragsarbeit, die aber

von großer Bedeutung für ihn war. Clara hatte schon früher

während ihrer Ausbildung im Atelier des Meisters gearbeitet.

Jetzt bereitete Rilke einen Vortrag über Rodin vor, der später

sein Rodin-Buch ergänzte. In Friedelhausen erreichte ihn Anfang

September ein Telegramm Rodins, dazu dessen Einladung, bei ihm in

Meudon zu wohnen.

Gleich im Anschluss an Friedelhausen also ging Rilke wieder nach Paris.

"Die Gräfin hatte Friedelhausen schon vor Rilkes Abreise verlassen müssen, und so berichtete er ihr: "aus den letzten schnellen Tagen im lieben grauen Schloß kamen viele Gedanken von mir zu Ihnen - das Leben sollte weitergehen mit seiner Art: das war das sicherste Mittel, Ihnen nahe zu sein. Man mußte beim Frühstück sitzen, als ob Sie jeden Augenblick eintreten könnten, und mittags zusammenkommen in Ihrem hohen Arbeitszimmer und abends still zusammensein in Ihrem lieben Namen. Und zwischendurch war manches; da kamen die ersten Korrekturbogen meines Stunden-Buches und wollten gelesen sein, und der Nachmittag brachte unsere Kant-Stunde, die am letzten Tage auch das Buch zu Ende führte, das wir uns vorgenommen hatten.

|

2010_03_27 Today's e-mail from "Abraham"

2002

[see

my thread of studying Abraham's 'The Vortex']

"Mining the moment for something

that feels good,

something to appreciate,

something to savor,

something to take in,

that's what your moments are about.

They're not about justifying your existence. It's justified. You exist.

It's not about proving your worthiness. It's done. You're worthy.

It's not about achieving success. You never get it done.

It's about "How much can this moment deliver to me?"

And some of you like them fast, some of you like them slow.

No one's taking score. You get to choose.

The only measurement is between my desire and my allowing.

And your emotions tell you everything about that. "

See also a newly posted video from 2007: No Gain in Pain from which I

copy in writing:

"....you're the reason that the river is going

fast

and you are the reason if you are going with it or not

You have total control in all of this

and nothing that you are doing has anything to do with anybody else's river

in other words: stay out of their boat and don't invite them in your boat

IN other words - the only awareness that you need to have

if you want to utilize the guidance-system that you

were born with [your feelings]

you want to know one thing and one thing only,

moment to moment, thought by thought: is this upstream or

downstream.

And then the next statement is: How can I make it more downstream.

How can I turn this thought and this feeling more downstream.

What can I do to soften the resistance,

what can I do to release the resistance a little more,

and trying harder is the wrong answer...

It's the letting go of the oars which makes the bliss [?].

It's trusting the process

We once wrote a book with the best title of any book that's ever been written.

Ask and it is given.

Life causes you to ask, and Source not only gives it to you,

Source literally becomes the vibrational essence

of that which you're asking for

[that's what "Spirit" in Godchannel

says about the nature of the Mother,

"my Will", "my Desire", "the magnetic essence"....]

and stands in such complete alignment with the ever expanding version of you

and offers a signal unto the Universe that Law of Attraction is responding

to

which creates the sensation within you of a current that is indescribable,

and when you allow yourself to move into the direction of that current,

you feel wonderful, and when you don't you don't ."

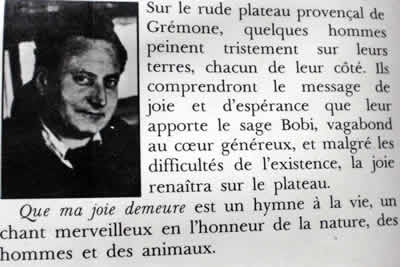

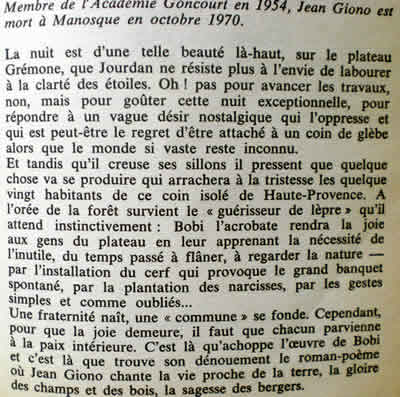

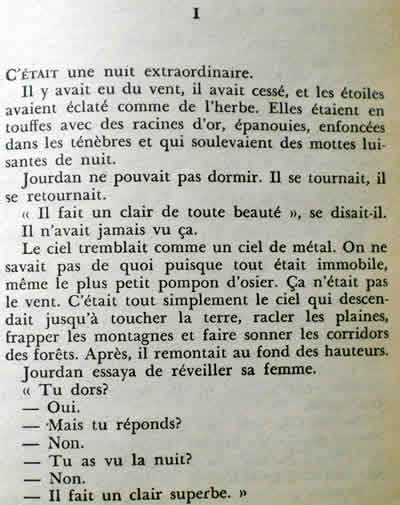

2010_03_28 Rilke's Letters and Jean Giono's

"Que ma joie demeure"

| 68 An Tora Homstroem - Paris

rue Cassette, am 16. Sept. 1907 [p. 233] ... Ich bin wie einer,

der Pilze sammelt und Heilkraeuter unter den Kraeutern; da sieht man

gebueckt und mit Geringem beschaeftigt aus, waehrend die Staemme ringsum

stehen und anbeten. Aber die zeit wird kommen, wo ich den Trank bereite.

Und die andere, wo ich ihn hinaufbringe, in dem alles verdichtet ist

und verbunden, das Giftigste und Toedlichste, um seiner Staerke willen;

hinaufbringe zu Gott, damit er seinen Durst stille und seinen Glanz

in seine Adern stroemen fuehle~~~

|

[see a report about this area and Jean Giono] and Wikipedia about Giono's Rencontres du Contadour p.11 Il y avait tant de lumière qu'on voyait le monde dans sa vraie vérité, non lus décharné de jour mais engraissé d'ombre et d'une couleur bein plus fine. L'oeil s'en réjouissait. L'apparence des choses n'avait plus de cruauté mais tout racontait une histoire, tout parlait doucement aux sens. La forêt la-bas était couchée dans le tiède des combes comme une gross pintade aux plumes luisantes. "Et, se dit Jourdan, j'aimerais bien qu'il me trouve en train de labourer." Depuis longtemps it attendait la venue d'un homme. Il ne savait pas qui. It ne savait pas d'ou il viendrait. Il ne savait pas s'il viendrait. Il le désirait seulement. C'est comme ça que parfois les choses se font et l'espérance humaine est un tel miracle qu'il ne faut pas s'étonner si parfois elle s'allume dans une tête sans savoir ni pourquoi ni comment. p.24 Il ne faut jamais expliquer. Ils sont bien plus contents les autres quand ils trouvent tout seuls. |

2010_04_05- Pesach-last day

| RILKE, LETTERS 120.

An Mimi Romanelli, Venise, ce 11 Mai 1910 127. An Clara

Rilke- s/s Ramses the Great, Luxor, am 18. Januar 1911 128. An Anton

Kippenberg Hotel al Havat, Helouan bei Kairo, am 28. Februar 1911 |

QUE MA JOIE DEMEURE

|

|

A similar shrub in

my son's garden, which I admired |

April 9-10, 2010, Shabbat

RILKE,

LETTERS

|

QUE MA JOIE DEMEURE p.46 |

|

|

|

|

|

April 17, 2010, Shabbat

RILKE, LETTERS 192. An Carossa

(Nov. 1913, probably Paris, Rue Campagne Premire)

|

Rilke: Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge 1910 [ with a dedication for me from Irene Sonnabend, 1991] .p.77-78 ...Denn da begriff ich noch nicht den Ruhm, diesen oeffentlichen Abbruch eines Werdenden, in dessen Bauplatz die Menge einbricht, ihm die Steine verschiebend. Junger Mensch irgendwo, in dem etwas aufsteigt, was ihn erschauern macht, nuetz es, dass dich keiner kennt. Und wenn sie dir widersprechen, die dich fuer nichts nehmen, und wenn sie dich ganz aufgeben, die, mit denen du umgehst, und wenn sie dich ausrotten wollen um deiner lieben Gedanken willen, was ist diese deutliche Gefahr, die dich zusammenhaelt in dir, gegen die listige Feindschaft spaeter des Ruhms, die dich unschaedlich macht, indem sie dich ausstreut. Bitte keinen, dass er von dir spraeche, nicht einmal veraechtlich. Und wenn die Zeit geht und du merkst, wie dein Name herumkommt unter den Leuten, nimm ihn nicht ernster als alles, was du in ihrem Munde findest. Denk: er ist schlecht geworden, und tu ihn ab. Nimm einen andern an, irgendeinen, damit Gott dich rufen kann in der Nacht. Und verbirg ihn vor allen.

p.83 Maman:

"

Ach Malte, wir gehen so hin, 76 ....ce ciel était fait

pour s'en aller, tel qu'il était, jusqu'a la fin du temps,

de l'espace et de la durée. Et celui qui aurait pu le peupler

d'une algue grosse |

On Independence Day/Nakba Day , April

20, 2010

a tiny clipping from Rilke's letter fell to the ground

- no date, no place, no addressee, no page number:

"Erfahrungen, durch die wir zusammenhaengen

moegen.

Wie leicht haben Sie mir jene Menschen lebhaft gemacht,

jeden in seiner Art bemueht,

ein Groesseres an die engen Umstaende zu gewoehnen,

in denen der Alltag auskommt.

Wenn es unsere Aufgabe sein sollte,

das Bewusstsein Gottes

auf eine unvergleichliche und unabsehbare Weise

in uns hervorzubringen,

so moechte, bei der Schwaeche des...."

Another tiny clipping from Rilke's

letter - discovered on May 9, 2010

- before April 14, 1910, Rome, no

addressee, no page number:

Ja, solang der Wunsch schwach ist,

ist er wie eine Haelfte und braucht das Erfuelltwerden wie eine zweite Haelfte,

um etwas Selbstaendiges zu sein.

Aber Wuensche koennen so wunderbar zu etwas ganzem, Vollem, Heilem auswachsen,

das sich gar nicht mehr ergaenzen laesst,

das nur noch aus sich heraus zunimmt

und sich formt und fuellt.

Manchmal koennte man meinen,

dies gerade waere die Ursache der Groesse und Intensitaet eines Lebens gewesen,

dass es sich mit zu grossen Wuenschen einliess,

die von innen wie ein Ressort Aktion auf Aktion, Wirkung nach Wirkung ins

Leben hinaus trieben,

die kaum mehr wussten, worauf sie urspruenglich gespannt waren,

und nur noch elementar, wie starkes, fallendes Wasser,

sich in Handlung und Herzlichkeit , in unmittelbares Dasein, in frohen Mut

umsetzten,

je nachdem das Geschehen und die Gelegenheit sie einschaltete.

...

Erzaehlte ich - ? nein: dass Adele Schopenhauers Briefe

meine Reiselektuere waren.

Was fuer ein ernstes heldisches Maedchen darin erscheint,

wie als Silhouette, zur Gestalt kommt es nicht.

|

1912, p.

381

|

June

19, 2010, before my visit to France from June 22-26, I dedicated 3 days to studying Giono's book: "QUE MA JOIE DEMEURE", While searching for all the terms and words which I didn't know in "Babylon", and - mostly in vain - for the mentioned places in "Google-Map", I also came across this webpage: JEAN GIONO L'homme

qui plantait des arbres

"La nouvelle de Jean Giono qui suit

a été écrite vers 1953 et n'est que peu connue

en France. Par contre, traduite en treize langues, elle a été

largement diffusée dans le monde entier et si appréciée

que de nombreuses questions ont été posées sur

la personnalité d'Elzéard Bouffier et sur la forêt

de Vergons, ce qui a permis de retrouver le texte. Si l'homme qui

plantait des chênes est le produit de l'imagination de l'auteur,

il y a eu effectivement dans cette région un énorme

effort de reboisement surtout depuis 1880. Cent mille hectares ont

été reboisés avant la première guerre

mondiale, surtout en pin noir d'Autriche et en mélèze

d'Europe, ce sont aujourd'hui de belles forêts qui ont effectivement

transformé le paysage et le régime des eaux. "Cher Monsieur, Quotes from this novel:

"Quand on se souvenait que tout était sorti des mains et de l'âme de cet homme - sans moyens techniques - on comprenait que les hommes pourraient être aussi efficaces que Dieu dans d'autres domaines que la destruction." "Il a trouvé un fameux moyen d'être heureux ! » |

|

|

Having savored the Jean Giono's novel about the man who planted trees, I feel pained once more for having failed so often in seeing my planted trees survive and grow. From my last endeavor (Jan.-Febr. 2010) one tree is blossoming now: the tiny Chinese Orange |

|

But

the pear-tree,

|

|

|

One

of the two vines which I planted also died, but the second one, which took much longer to come out, is alive so far. Thank you!

Also,

|

|

See

also Rilke's letters to a young poet - what I call: Rilke's Prophecy about

Love - in German, though I once translated them into Hebrew (where is it?)

June 22, 2011,

In my "favorites" I come again and again across

Rilke's favored master-novel 'Niels Lyhne' (1880)

by Jens Peter Jacobsen (1847-1885)

translated from

Danish into English.

To read 245 pages online is difficult,

but more difficult is the content,

though very well sculpted, indeed.

I want to copy the first and the last pages and NOT comment on them.

It should be obvious, that for

one who "celebrates what is right in the World",

why such difficulty to live , though it WAS "my cup of tea" for

most of my life,

is not helpful in "healing myself into wholeness and - by extension -

Creation",

which also implies, that I am the creator of my life, yes of my humankind!.

|

SHE had the black, luminous eyes

of the Blid family, with delicate, straight eyebrows; she had their

boldly shaped nose, their strong chin, and full lips. The curious line

of mingled pain and sensuousness about the corners of her mouth was

likewise an inheritance from them, and so were the restless movements

of her head. But her cheek was pale, her hair was soft as silk and was

wound smoothly around her head.

Not so the Blids; their coloring was of roses and bronze. Their hair was rough and curly, heavy as a mane, and their full, deep, resonant voices bore out the tales told of their forefathers, whose noisy hunting parties, solemn morning prayers, and thousand and one amorous adventures were matters of family tradition. Her voice was languid and colorless. I am describing her as she was at seventeen. A few years later, after she had been married, her voice gained fullness, her cheek took on a fresher tint, and her eye lost some of its luster, but seemed even larger and more intensely black. At seventeen she did not at all resemble her brothers and sisters; nor was there any great intimacy between herself and her parents. The Blid family were practical folk who accepted things as they were; they did their p17 work, slept their sleep, and never thought of demanding any diversions beyond the harvest home and three or four Christmas parties. They never passed through any religious experiences, but they would no more have dreamed of not rendering unto God what was God's than they would have neglected to pay their taxes. Therefore they said their evening prayers, went to church at Easter and Whitsun, sang their hymns on Christmas Eve, and partook of the Lord's Supper twice a year. They had no particular thirst for knowledge. As for their love of beauty, they were by no means insensible to the charm of little sentimental ditties, and when summer came with thick, luscious grass in the meadows and grain sprouting in broad fields, they would sometimes say to one another that this was a fine time for traveling about the country, but their natures had nothing of the poetic; beauty never stirred any raptures in them, and they were never visited by vague longings or day-dreams. Bartholine was not of their kind. She had no interest in the affairs of the fields and the stables, no taste for the dairy and the kitchen--none whatever. She loved poetry. She lived on poems, dreamed poems, and put her faith in them above everything else in the world. Parents, sisters and brothers, neighbors and friends--none of them ever said a word that was worth listening to. Their thoughts never rose above their land and their business; their eyes never sought anything beyond the conditions and affairs that were right before them. But the poems! They teemed with new ideas and profound truths about life in the great outside world, where grief was black, and joy was red; they glowed with images, foamed and sparkled with rhythm and p18 rhyme. They were all about young girls, and the girls were noble and beautiful--how noble and beautiful they never knew themselves. Their hearts and their love meant more than the wealth of all the earth; men bore them up in their hands, lifted them high in the sunshine of joy, honored and worshiped them, and were delighted to share with them their thoughts and plans, their triumphs and renown. They would even say that these same fortunate girls had inspired all the plans and achieved all the triumphs. Why might not she herself be such a girl? They were thus and so--and they never knew it themselves. How was she to know what she really was? And the poets all said very plainly that this was life, and that it was not life to sit and sew, work about the house, and make stupid calls. When all this was sifted down, it meant little beyond a slightly morbid desire to realize herself, a longing to find herself, which she had in common with many other young girls with talents a little above the ordinary. It was only a pity that there was not in her circle a single individual of sufficient distinction to give her the measure of her own powers. There was not even a kindred nature. So she came to look upon herself as something wonderful, unique, a sort of exotic plant that had grown in these ungentle climes and had barely strength enough to unfold its leaves; though in more genial warmth, under a more powerful sun, it might have shot up, straight and tall, with a gloriously rich and brilliant bloom. Such was the image of her real self that she carried in her mind. She dreamed a thousand dreams of those sunlit regions and was consumed with longing for this other and richer self, forgetting--what is so easily forgotten--that even the p19 fairest dreams and the deepest longings do not add an inch to the stature of the human soul. One fine day a suitor came to her. Young Lyhne of Lönborggaard was the man,and he was the last male scion of a family whose members had for three generations been among the most distinguished people in the country. As burgomasters, revenue collectors, or royal commissioners, often rewarded with the title of councillor of justice, the Lyhnes in their maturer years had served king and country with diligence and honor. In their younger days they had traveled in France and Germany, and these trips, carefully planned and carried out with great thoroughness, had enriched their receptive minds with all the scenes of beauty and the knowledge of life that foreign lands had to offer. Nor were these years of travel pushed into the background, after their return, as mere reminiscences, like the memory of a feast after the last candle has burned down and the last note of music has died away. No, life in their homes was built on these years; the tastes awakened in this manner were not allowed to languish, but were nourished and developed by every means at their command. Rare copper plates, costly bronzes, German poetry, French juridical works, and French philosophy were everyday matters and common topics in the Lyhne households. Their bearing had an old-fashioned ease, a courtly graciousness, which contrasted oddly with the heavy majesty and awkward pomposity of the other county families. Their speech was well rounded, delicately precise, a little marred, perhaps, by rhetorical affectation, yet it somehow went well with those large, broad figures with their domelike foreheads, their bushy hair growing far back on their temples, their calm, smiling eyes, and p20 slightly aquiline noses. The lower part of the face was too heavy, however, the mouth too wide, and the lips much too full. Young Lyhne showed all these physical traits,

|

On

a gloomy day in March he was shot in the chest.

Hjerrild, who was a physician in the hospital, had him put into a small room where there were only four beds. One of the men in there had been shot in the spine and lay quite still. Another was wounded in the breast and p241 lay talking deliriously for hours at a time in quick, abrupt phrases. The third, who lay nearest Niels, was a great, strong peasant lad with fat, round cheeks; he had been struck in the brain by a fragment of a shell, and incessantly, hour after hour, about every half minute, he would lift his right arm and his right leg simultaneously and then let them fall again, accompanying his movements with a loud but dull and hollow "Hah-ho!" always in the same measure, always exactly the same, "Hah" when he lifted his limbs, "ho" when he let them fall. There Niels Lyhne lay. The bullet had entered his right lung and had not come out again. In war not much circumlocution can be used, and he was told he had but little chance of life. He was surprised; for he did not feel as though he were dying, and his wound did not pain him much. But soon a faintness came over him and warned him that the doctor was right. So this was the end. He thought of Gerda, he thought of her constantly the first day, but he was always disturbed by the strange, cool look in her eyes the last time he had taken her in his arms. How beautiful it would have been, how poignantly beautiful, if she had clung to him to the very last and had sought his eye till her own was glazed in death; if she had been content to breathe out her life upon the heart that loved her so well instead of turning away from him at the last moment to save herself over into more life and yet more life! On the second day in the hospital, Niels felt more and more oppressed by the heavy atmosphere in the room, and his longing for fresh air was strangely interwined in his mind with the desire to live. After all, there had been so much in life that was beautiful, he p242 thought, as he remembered the fresh breeze along the shore at home, the cool soughing of the wind in the beech forests of Sjaslland, the pure mountain air of Clarens, and the evening zephyrs of Lake Garda. But when he began to think of human beings, his soul sickened again. He summoned them in review before him, one by one, and they all passed and left him alone, and not one stayed with him. But how far had he held fast to them? Had he been true? He had only been slower in letting go, that was all. No, it was not that. It was the dreary truth that a soul is always alone. Every belief in the fusing of soul with soul was a lie. Not your mother who took you on her lap, nor your friend, nor yet the wife who slept on your heart Toward evening, inflammation set in, and the pain of his wound increased. Hjerrild came and sat by him for a few minutes in the evening, and at midnight he returned and stayed a long time. Niels was suffering intensely and moaned with pain. "A word in all seriousness, Lyhne," said Hjerrild. "Do you want to see a clergyman?" "I have no more to do with clergymen than you have," Niels whispered angrily. "Never mind me! I am alive and well. Don't lie there and torture yourself with your opinions. People who are about to die have no opinions, and those they have don't matter. Opinions are only to live by--in life they can do some good, but what does it matter whether you die with one opinion or another? See here, we all have bright, tender memories from our childhood; I have seen scores of people die, and it always comforts them to bring back those memories. Let us be honest! No matter what we p243 call ourselves, we can never quite get that God out of heaven; our brain has fancied Him up there too often, the picture has been rung into it and sung into it from the time we were little children." Niels nodded. Hjerrild bent down to catch his words if he wished to say anything. "You are very good," Niels whispered, "but"--and he shook his head decisively. The room was still a long time except for the peasant lad's everlasting "Hah-ho!" hammering the hours to pieces. Hjerrild rose. "Good-by, Lyhne," he said. "After all, it is a noble death to die for our poor country." "Yes," said Niels, "and yet this is not the way we dreamed of doing our part that time long, long ago." Hjerrild left him. When he came into his own room, he stood a long while by the window looking up at the stars. "If I were God," he said under his breath, and in his thoughts he continued, "I would much rather save the man who was converted at the last moment." The pain in Niels's wound grew more and more intense; it tore and clutched at his breast, it persisted without mercy. What a relief it would have been if he had had a god to whom he could have moaned and prayed! Toward morning he grew delirious, the inflammation was progressing rapidly. So it went on for two more days and two more nights. The last time Hjerrild saw Niels Lyhne he was babbling of his armor and of how he must die standing. And at last he died the death--the difficult death. |

…..

Aber nach alledem und nach gewissen bangen und tiefen Ereignissen,

die alles, was war, eigentuemlich verknuepft und gedeutet haben, muesste,

muss eine Zeit fuer mich kommen, mit meinem Erleben allein zu sein,

ihm zu gehoeren, es umzubilden: denn schon drueckt mich all das Unverwandelte

und verwirrt mich: es war nur Ausdruck fuer diesen Zustand,

dass ich mich mehr als je sehnte, diesen Fruehling, der an alles heranreichte

und ruehrte, wie einen Beruf auf mich zu nehmen: denn er waere zum

aeussersten Anlass fuer so vieles geworden, was nur auf einen Anstoss

wartet. Ich glaube nicht, dass ich mich taeusche, wenn ich meine,

dass mein Alter (ich werde in diesemJahre einundreissig) und alle

anderen Umstaende dafuer sprechen, dass ich, falls ich mich jetzt

zu meinen naechsten Fortschritten zusammenfassen duerfte, ein paar

Arbeiten zustande bringen koennte, die gut waeren, mir innerlich weiter

helfen und vielleicht auch aeusserlich eine Sicherung meines Lebens

anbahnen koennten, die durch die bisherigen Buecher nicht gegeben,

aber doch gleichsam fuer spaeter nicht ganz abgesprochen ist~~~

Aber nach alledem und nach gewissen bangen und tiefen Ereignissen,

die alles, was war, eigentuemlich verknuepft und gedeutet haben, muesste,

muss eine Zeit fuer mich kommen, mit meinem Erleben allein zu sein,

ihm zu gehoeren, es umzubilden: denn schon drueckt mich all das Unverwandelte

und verwirrt mich: es war nur Ausdruck fuer diesen Zustand,

dass ich mich mehr als je sehnte, diesen Fruehling, der an alles heranreichte

und ruehrte, wie einen Beruf auf mich zu nehmen: denn er waere zum

aeussersten Anlass fuer so vieles geworden, was nur auf einen Anstoss

wartet. Ich glaube nicht, dass ich mich taeusche, wenn ich meine,

dass mein Alter (ich werde in diesemJahre einundreissig) und alle

anderen Umstaende dafuer sprechen, dass ich, falls ich mich jetzt

zu meinen naechsten Fortschritten zusammenfassen duerfte, ein paar

Arbeiten zustande bringen koennte, die gut waeren, mir innerlich weiter

helfen und vielleicht auch aeusserlich eine Sicherung meines Lebens

anbahnen koennten, die durch die bisherigen Buecher nicht gegeben,

aber doch gleichsam fuer spaeter nicht ganz abgesprochen ist~~~