|

InteGRATion into

GRATeFULLness

Singing&Sounding keeps me Sound

Lullaby

|

2007_05_27 [If I should ever loose you] |

lyrics:

Rainer Maria Rilke So far I couldn't discover the original German poem translation to Hebrew: author not known |

tune: Ronya Shai my daughter's sister in law 1987 |

from

"The Songs of Songs" page 2

|

![]()

2010

"Everything is blooming most

recklessly;

if it were voices instead of colors,

there would be an unbelievable shrieking into the heart of the night."

One

of 36 quotes from Rainer Maria Rilke

April 10, 2010

While immersed in excerpting

Rilke's letters from my paper-cuttings,

I want to copy-paste

from the Internet "the Letters to a Young Poet"

and within them what I call "the prophecy about Love"

"Und diese menschlichere Liebe

(die unendlich ruecksichtsvoll und leise, und gut und klar in Binden

und Loesen sich vollziehen wird)

wird jener aehneln, die wir ringend und muehsam vorbereiten,

der Liebe, die darin beteht,

dass zwei Einsamkeiten einander schuetzen, grenzen und gruessen."

|

An

Franz Xaver Kappus

Paris am 17. Februar 1903 Sehr geehrter Herr,

Darum retten Sie sich vor den allgemeinen

Motiven zu denen, die Ihnen Ihr eigener Alltag bietet; schildern Sie

Ihre Traurigkeiten und Wünsche, die vorübergehenden Gedanken

und den Glauben an irgendeine Schönheit - schildern Sie das alles

mit inniger, stiller, demütiger Aufrichtigkeit und gebrauchen Sie,

um sich auszudrücken, die Dinge Ihrer Umgebung, die Bilder Ihrer

Träume und die Gegenstände ihrer Erinnerung. Nehmen Sie sie, wie sie klingt, an, ohne

daran zu deuten. Vielleicht erweist es sich, daß Sie berufen sind,

Künstler zu sein. Dann nehmen Sie das Los auf sich, und tragen

Sie es, seine Last und seine Größe, ohne je nach dem Lohne

zu fragen, der von außen kommen könnte. Denn der Schaffende

muß eine Welt für sich sein und alles in sich finden und

in der Natur, an die er sich angeschlossen hat.

|

An Franz

Xaver Kappus

Viareggio bei Pisa (Italien), am 5. April 1903 Sie müssen es mir verzeihen,

lieber und geehrter Herr, daß ich Ihres Briefes vom 24. Februar

erst heute dankbar gedenke: ich war die ganze Zeit leidend, nicht gerade

krank, aber von einer influenza-artigen Mattigkeit bedrückt, die

mich unfähig machte zu allem. Und schließlich, als es gar

nicht anders werden wollte, fuhr ich an dieses südliche Meer, dessen

Wohltun mir schon einmal geholfen hat. Aber ich bin noch nicht gesund,

das Schreiben fällt mir schwer, und so müssen Sie diese wenigen

Zeilen nehmen für mehr.

Es fällt mir ein, ob Sie seine Werke

kennen. Sie können sich dieselben leicht verschaffen, denn ein

Teil derselben ist in Reclams Universal-Bibliothek in sehr guter Übertragung

erschienen. Verschaffen Sie sich das Bändchen «Sechs Novellen»

von J. P. Jacobsen und seinen Roman «Niels Lyhne», und beginnen

Sie des ersten Bändchens erste Novelle, welche «Mogens»

heißt. Eine Welt wird über Sie kommen, das Glück, der

Reichtum, die unbegereifliche Größe einer Welt. Leben Sie

eine Weile in diesen Büchern, lernen Sie davon, was Ihnen lernenswert

scheint, aber vor allem lieben Sie sie. Diese Liebe wird Ihnen tausend-

und tausendmal vergolten werden, und wie Ihr Leben auch werden mag,

- sie wird, ich bin dessen gewiß, durch das Gewebe Ihres Werdens

gehen als einer von den wichtigsten Fäden unter allen Fäden

Ihrer Erfahrungen, Enttäuschungen und Freuden. Rainer Maria Rilke |

|

Brief

drei: An Franz Xaver Kappus Viareggio bei Pisa (Italien), am 23. April 1903

Geben Sie jedesmal sich und Ihrem Gefühl recht,

jeder solche Auseinandersetzung, Besprechung oder Einführung

gegenüber; sollten Sie doch unrecht haben, so wird das natürliche

Wachstum Ihres innern Lebens Sie langsam und mit der Zeit zu anderen

Erkenntnissen führen. Lassen Sie Ihren Urteilen die eigene stille,

ungestörte Entwicklung, die, wie jeder Fortschritt, tief aus

innen kommen muß und durch nichts gedrängt oder beschleunigt

werden kann. Alles ist austragen und dann

gebären. Jeden Eindruck und jeden Keim eines Gefühls ganz

in sich, im Dunkel, im Unsagbaren, Unbewußten, dem eigenen Verstande

Unerreichbaren sich vollenden lassen und mit tiefer Demut und Geduld

die Stunde der Niederkunft einer neuen Klarheit abwarten: das allein

heißt künstlerisch leben: im Verstehen wie im Schaffen.

Leben Sie wohl! Ihr: Rainer Maria Rilke |

An

Franz Xaver Kappus z. Zt. Worpswede bei Bremen, am 16. Juli 1903

Vielleicht tragen Sie ja in sich die Möglichkeit,

zu bilden und zu formen, als eine besonders selige und reine Art des

Lebens; erziehen Sie sich dazu, - aber nehmen Sie das, was kommt,

in großem Vertrauen hin, und wenn es nur aus Ihrem Willen kommt,

aus irgendeiner Not Ihres Innern, so nehmen Sie es auf sich und hassen

Sie nichts. Das Geschlecht ist schwer; ja. Aber es ist Schweres, was

uns aufgetragen wurde, fast alles Ernste ist schwer, und alles ist

ernst. Wenn Sie das nur erkennen und dazu kommen, aus sich, aus Ihrer

Erfahrung und Kindheit und Kraft heraus ein ganz eigenes (von Konvention

und Kindheit und Sitte nicht beeinflußtes) Verhältnis zu

dem Geschlecht zu erringen, dann müssen Sie nicht mehr fürchten,

sich zu verlieren und unwürdig zu werden Ihres besten Besitzes.

Suchen Sie sich mit ihnen irgendeine schlichte und

treue Gemeinsamkeit, die sich nicht notwendig verändern muß,

wenn Sie selbst anders und anders werden; lieben Sie an ihnen das

Leben in einer fremden Form und haben Sie Nachsicht gegen die alternden

Menschen, die das Alleinsein fürchten, zu dem Sie Vertrauen haben.

Vermeiden Sie, jenem Drama, das zwischen Eltern und Kindern immer

ausgespannt ist, Stoff zuzuführen; es verbraucht viel Kraft der

Kinder und zehrt die Liebe der Alten auf, die wirkt und wärmt,

auch wenn sie nicht begreift. Verlangen Sie keinen Rat von ihnen und

rechnen Sie mit keinem Verstehen; aber glauben Sie an eine Liebe,

die für Sie aufbewahrt wird wie eine Erbschaft, und vertrauen

Sie, daß in dieser Liebe eine Kraft ist und ein Segen, aus dem

Sie nicht herausgehen müssen, um ganz weit zu gehen! Rainer Maria Rilke |

An

Franz Xaver Kappus Rom, am 29. Oktober 1903 Lieber und geehrter Herr, Ihr: Rainer Maria Rilke |

An

Franz Xaver Kappus Rom, am 23. Dezember 1903 Mein lieber Herr Kappus, Wenn Sie aber erkennen, daß er in Ihrer Kindheit

nicht war, und nicht vorher, wenn Sie ahnen, daß Christus getäuscht

worden ist von seiner Sehnsucht und Muhammed betrogen von seinem Stolze,

- und wenn Sie mit Schrecken fühlen, daß er auch jetzt

nicht ist, in dieser Stunde da wir von ihm reden, - was berechtigt

Sie dann, ihn, welcher niemals war, wie einen Vergangenen zu vermissen

und zu suchen, als ob er verlören wäre? Ihr: Rainer Maria Rilke |

An

Franz Xaver Kappus Rom, am 14. Mai 1904 Mein lieber Herr Kappus,

Darum können junge Menschen, die Anfänger

in allem sind, die Liebe noch nicht: sie müssen sie lernen. Mit

dem ganzen Wesen, mit allen Kräften, versammelt um ihr einsames,

banges, aufwärts schlagendes Herz, müssen sie lieben lernen. Dieser Fortschritt wird das Liebe-Erleben, das jetzt

voll Irrung ist (sehr gegen den Willen der überholten Männer

zunächst), verwandeln, von Grund aus verändern, zu einer

Beziehung umbilden, die von Mensch zu Mensch gemeint ist, nicht mehr

von Mann zu Weib. Und diese menschlichere Liebe (die unendlich rücksichtsvoll

und leise, und gut und klar in Binden und Lösen sich vollziehen

wird) wird jener ähneln, die wir ringend und mühsam vorbereiten,

der Liebe, die darin besteht, daß zwei Einsamkeiten einander

schützen, grenzen und grüßen. Ihr: Rainer Maria Rilke Sonett Durch mein Leben zittert ohne Klage, Öfter aber kreuzt die große

Frage Und dann sinkt ein Leid auf mich,

so trübe Meine Hände tasten dann nach

Liebe, (Franz Xaver Kappus) |

An

Franz Xaver Kappus Borgeby gård, Flädie, Schweden, am 12. August 1904 Mein lieber Herr Kappus,

Beobachten Sie sich nicht zu sehr. Ziehen Sie nicht

zu schnelle Schlüsse aus dem, was Ihnen geschieht; lassen Sie

es sich einfach geschehen. Sie kommen sonst zu leicht dazu, mit Vorwürfen

(das heißt: moralisch) auf Ihre Vergangenheit zu schauen, die

natürlich an allem, was Ihnen jetzt begegnet, mitbeteiligt ist.

Was aus den Irrungen, Wünschen und Sehnsüchten Ihrer Knabenzeit

in Ihnen wirkt, ist aber nicht das, was Sie erinnern und verurteilen.

Die außergewöhnlichen Verhältnisse einer einsamen

und hilflosen Kindheit sind so schwer, so kompliziert, so vielen Einflüssen

preisgegeben und zugleich so ausgelöst aus allen wirklichen Lebenszusammenhängen,

daß, wo ein Laster in sie eintritt, man es nicht ohne weiteres

Laster nennen darf. Man muß überhaupt mit den Namen so

vorsichtig sein; es ist so oft der Name eines Verbrechens, an dem

ein Leben zerbricht, nicht die namenlose und persönliche Handlung

selbst, die vielleicht eine ganz bestimme Notwendigkeit dieses Lebens

war und von ihm ohne Mühe aufgenommen werden könnte. Und

der Kraft-Verbrauch scheint Ihnen nur deshalb so groß, weil

Sie den Sieg überschätzen; nicht er ist das «Große»,

das Sie meinen geleistet zu haben, obwohl Sie recht haben mit Ihrem

Gefühl; das Große ist, daß schon etwas da war, was

Sie an Stelle jenes Betruges setzen durften, etwas Wahres und Wirkliches.

Ohne dieses wäre auch Ihr Sie nur eine moralische Reaktion gewesen,

ohne weite Bedeutung, so aber ist er ein Abschnitt Ihres Lebens geworden.

Ihres Lebens, lieber Herr Kappus, an das ich mit so vielen Wünschen

denke. Erinnern Sie sich, wie sich dieses Leben aus der Kindheit heraus

nach dem «Großen» gesehnt hat? Ich sehe, wie es

sich jetzt von den Großen fort nach den Größeren

sehnt. Darum hört es nicht auf, schwer zu sein, aber darum wird

es auch nicht aufhören zu wachsen. Rainer Maria Rilke |

An

Franz Xaver Kappus Furuborg, Jonsered, in Schweden am 4. November 1904 Mein lieber Herr Kappus, Ihr: Rainer Maria Rilke |

An

Franz Xaver Kappus Paris, am zweiten Weihnachtstage 1908 Sie sollen wissen, lieber Herr Kappus, wie froh ich war, diesen schönen Brief von Ihnen zu haben. Die Nachrichten, die Sie mir geben, wirklich und aussprechbar, wie sie nun wieder sind, scheinen mir gut, und je länger ichs bedachte, desto mehr empfand ich sie als tatsächlich gute. Dieses wollte ich Ihnen eigentlich zum Weihnachtsabend schreiben; aber über der Arbeit, in der ich diesen Winter vielfach und ununterbrochen lebe, ist das alte Fest so schnell herangekommen, daß ich kaum mehr Zeit hatte, die nötigsten Besorgungen zu machen, viel weniger zu schreiben. Aber gedacht hab ich an Sie in dieses Festtagen oft und mir vorgestellt, wie still Sie sein müssen in Ihrem einsamen Fort zwischen den leeren Bergen, über die sich jene großen südlichen Winde stürzen, als wollten Sie sie in großen Stücken verschlingen. Die Stille muß immens sein, in der solche Geräusche und Bewegungen Raum haben, und wenn man denkt, daß zu allem noch des entferntesten Meeres Gegenwart hinzukommt und mittönt, vielleicht als der innerste Ton in dieser vorhistorischen Harmonie, so kann man Ihnen nur wünschen, daß Sie vertrauensvoll und geduldig die großartige Einsamkeit an sich arbeiten lassen, die nicht mehr aus Ihrem Leben wird zu streichen sein; die in allem, was Ihnen zu erleben und zu tun bevorsteht, als ein anonymer Einfluß fortgesetzt und leise entscheidend wirken wird, etwa wie in uns Blut von Vorfahren sich unablässig bewegt und sich mit unserm eigenen zu dem Einzigen, nicht Wiederholbaren zusammensetzt, das wir an jeder Wendung unseres Lebens sind. Ja: ich freue mich, daß Sie diese feste, sagbare Existenz mit sich haben, diesen Titel, diese Uniform, diesen Dienst, alles dieses Greifbare und Beschränkte, das in solchen Umgebungen mit einer gleich isolierten nicht zahlreichen Mannschaft Ernst und Notwendigkeit annimmt, über das Spielerische und Zeithinbringende des militärischen Berufs hinaus eine wachsame Verwendung bedeutet und eine selbständige Aufmerksamkeit nicht nur zuläßt, sondern geradezu erzieht. Und daß wir in Verhältnissen sind, die an uns arbeiten, die uns vor große natürliche Dinge stellen von Zeit zu Zeit, das ist alles, was not tut. Auch die Kunst ist nur eine Art zu leben, und man kann sich, irgendwie lebend, ohne es zu wissen, auf sie vorbereiten; in jedem Wirklichen ist man ihr näher und benachbarter als in den unwirklichen halbartistischen Berufen, die, indem sie eine Kunstnähe vorspiegeln, das Dasein aller Kunst praktisch leugnen und angreifen, wie etwa der ganze Journalismus es tut und fast alle Kritik und dreiviertel dessen, was Literatur heißt und heißen will. Ich freue mich, mit einem Wort, daß Sie die Gefahr, dahinein zu geraden, überstanden haben und irgendwo in einer rauhen Realität einsam und mutig sind. Möchte das Jahr, das bevorsteht, Sie darin erhalten und bestärken.

Rainer Maria Rilke |

Aug.

17, 2010: I want to soon complete this composition |

See more about Rilke on the Song Page: Da neigt sich die Stunde |

Dennis Hopper reads from these letters in English,

...the parts about how to accept one's vocation as a poet and how to fulfil

it.

[A newsletter from the Rilke Association informed

me of this, on Sept. 10, 2010:

Im Mai diesen Jahres starb der Schauspieler Dennis Hopper. Seine ersten Auftritte

hatte er

an der Seite von James Dean in “...denn sie wissen nicht, was sie tun”

und “Giganten”, den

Gipfel der Berühmtheit erreichte er 1969 als “Billy” im Roadmovie

“Easy Rider”, bei dem er

auch für Regie und Drehbuch verantwortlich war. Weniger bekannt ist,

dass Dennis Hopper

auch ein großer Anhänger von Rilke war.

2007 sagte er in einem Interview mit dem

Fernsehsender Arte auf die Frage ob Rilke noch zeitgemäß sei:

Für mich gibt es kein besseres Buch

über das künstlerische Schaffen.”

The letter to

a young poet - in English on-line:

|

Letter

One Paris February 17, 1903 Dear Sir, With this note as a preface, may I just tell you that your verses have no style of their own, although they do have silent and hidden beginnings of something personal. I feel this most clearly in the last poem, "My Soul." There, something of your own is trying to become word and melody. And in the lovely poem "To Leopardi" a kind of kinship with that great, solitary figure does perhaps appear. Nevertheless, the poems are not yet anything in themselves, not yet anything independent, even the last one and the one to Leopardi. Your kind letter, which accompanied them, managed to make clear to me various faults that I felt in reading your verses, though I am not able to name them specifically. You ask whether your verses are any good. You ask me. You have asked others before this. You send them to magazines. You compare them with other poems, and you are upset when certain editors reject your work. Now (since you have said you want my advice) I beg you to stop doing that sort of thing. You are looking outside, and that is what you should most avoid right now. No one can advise or help you - no one. There is only one thing you should do. Go into yourself. Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depths of your heart; confess to yourself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write. This most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write? Dig into yourself for a deep answer. And if this answer rings out in assent, if you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple "I must," then build your life in accordance with this necessity; your while life, even into its humblest and most indifferent hour, must become a sign and witness to this impulse. Then come close to Nature. Then, as if no one had ever tried before, try to say what you see and feel and love and lose. Don't write love poems; avoid those forms that are too facile and ordinary: they are the hardest to work with, and it takes great, fully ripened power to create something individual where good, even glorious, traditions exist in abundance. So rescue yourself from these general themes and write about what your everyday life offers you; describe your sorrows and desires, the thoughts that pass through your mind and your belief in some kind of beauty - describe all these with heartfelt, silent, humble sincerity and, when you express yourself, use the Things around you, the images from your dreams, and the objects that you remember. If your everyday life seems poor, don't blame it; blame yourself; admit to yourself that you are not enough of a poet to call forth its riches; because for the creator there is not poverty and no poor, indifferent place. And even if you found yourself in some prison, whose walls let in none of the world's sounds - wouldn't you still have your childhood, that jewel beyond all price, that treasure house of memories? Turn your attentions to it. Try to raise up the sunken feelings of this enormous past; your personality will grow stronger, your solitude will expand and become a place where you can live in the twilight, where the noise of other people passes by, far in the distance. - And if out of this turning-within, out of this immersion in your own world, poems come, then you will not think of asking anyone whether they are good or not. Nor will you try to interest magazines in these works: for you will see them as your dear natural possession, a piece of your life, a voice from it. A work of art is good if it has arisen out of necessity. That is the only way one can judge it. So, dear Sir, I can't give you any advice but this: to go into yourself and see how deep the place is from which your life flows; at its source you will find the answer to the question whether you must create. Accept that answer, just as it is given to you, without trying to interpret it. Perhaps you will discover that you are called to be an artist. Then take the destiny upon yourself, and bear it, its burden and its greatness, without ever asking what reward might come from outside. For the creator must be a world for himself and must find everything in himself and in Nature, to whom his whole life is devoted. But after this descent into yourself and into your solitude, perhaps you will have to renounce becoming a poet (if, as I have said, one feels one could live without writing, then one shouldn't write at all). Nevertheless, even then, this self-searching that I as of you will not have been for nothing. Your life will still find its own paths from there, and that they may be good, rich, and wide is what I wish for you, more than I can say What else can I tell you? It seems to me that everything has its proper emphasis; and finally I want to add just one more bit of advice: to keep growing, silently and earnestly, through your while development; you couldn't disturb it any more violently than by looking outside and waiting for outside answers to question that only your innermost feeling, in your quietest hour, can perhaps answer. It was a pleasure for me to find in your letter the name of Professor Horacek; I have great reverence for that kind, learned man, and a gratitude that has lasted through the years. Will you please tell him how I feel; it is very good of him to still think of me, and I appreciate it. The poems that you entrusted me with I am sending back to you. And I thank you once more for your questions and sincere trust, of which, by answering as honestly as I can, I have tried to make myself a little worthier than I, as a stranger, really am. Yours very truly, Letter Two You must pardon me, dear Sir, for waiting until today to gratefully remember your letter of February 24: I have been unwell all this time, not really sick, but oppressed by an influenza-like debility, which has made me incapable of doing anything. And finally, since it just didn't want to improve, I came to this southern sea, whose beneficence helped me once before. But I am still not well, writing is difficult, and so you must accept these few lines instead of your letter I would have liked to send. Of course, you must know that every letter of yours will always give me pleasure, and you must be indulgent with the answer, which will perhaps often leave you empty-handed; for ultimately, and precisely in the deepest and most important matters, we are unspeakably alone; and many things must happen, many things must go right, a whole constellation of events must be fulfilled, for one human being to successfully advise or help another. Today I would like to tell you just two more things: Irony: Don't let yourself be controlled by it, especially during uncreative moments. When you are fully creative, try to use it, as one more way to take hold of life. Used purely, it too is pure, and one needn't be ashamed of it; but if you feel yourself becoming too familiar with it, if you are afraid of this growing familiarity, then turn to great and serious objects, in front of which it becomes small and helpless. Search into the depths of Things: there, irony never descends - and when you arrive at the edge of greatness, find out whether this way of perceiving the world arises from a necessity of your being. For under the influence of serious Things it will either fall away from you (if it is something accidental), or else (if it is really innate and belongs to you) it will grow strong, and become a serious tool and take its place among the instruments which you can form your art with. And the second thing I want to tell you today is this: Of all my books, I find only a few indispensable, and two of them are always with me, wherever I am. They are here, by my side: the Bible, and the books of the great Danish poet Jens Peter Jacobsen. Do you know his works? It is easy to find them, since some have been published in Reclam's Universal Library, in a very good translation. Get the little volume of Six Stories by J. P. Jacobsen and his novel Niels Lyhne, and begin with the first story in the former, which is called "Mogens." A whole world will envelop you, the happiness, the abundance, the inconceivable vastness of a world. Live for a while in these books, learn from them what you feel is worth learning, but most of all love them. This love will be returned to you thousands upon thousands of times, whatever your life may become - it will, I am sure go through the while fabric of your becoming, as one of the most important threads among all the threads of your experiences, disappointments, and joys. If I were to say who has given me the greatest experience of the essence of creativity, its depths and eternity, there are just two names I would mention: Jacobsen, that great, great poet, and Auguste Rodin, the sculptor, who is without peer among all artists who are alive today. - And all success upon your path! Yours, Rainer Marie Rilke

Letter Three You gave me much pleasure, dear Sir, with your Easter letter; for it brought much good news of you, and the way you spoke about Jacobsen's great and beloved art showed me that I was not wrong to guide your life and its many question to this abundance. Now Niels Lyhne will open to you, a book of splendors and depths; the more often one reads it, the more everything seems to be contained within it, from life's most imperceptible fragrances to the full, enormous taste of its heaviest fruits. In it there is nothing that does not seem to have been understood, held lived, and known in memory's wavering echo; no experience has been too unimportant, and the smallest event unfolds like a fate, and fate itself is like a wonderful, wide fabric in which every thread is guided by an infinitely tender hand and laid alongside another thread and is held and supported by a hundred others. You will experience the great happiness of reading this book for the first time, and will move through its numberless surprises as if you were in a new dream. But I can tell you that even later on one moves through these books, again and again, with the same astonishment and that they lose none of their wonderful power and relinquish none of the overwhelming enchantment that they had the first time one read them. One just comes to enjoy them more and more, becomes more and more grateful, and somehow better and simpler in one's vision, deeper in one's faith in life, happier and greater in the way one lives. - And later on , you will have to read the wonderful book of the fate and yearning of Marie Grubbe, and Jacobsen's letters and journals and fragments, and finally his verses which (even if they are just moderately well translated) live in infinite sound. (For this reason I would advise you to buy, when you can, the lovely Complete Edition of Jacobsen's works, which contains all of these. It is in there volumes, well translated, published by Eugen Diederichs in Leipzig, and costs, I think, only five or six marks per volume.) In your opinion of "Roses should have been here . . . " (that work of such incomparable delicacy and form) you are of course quite, quite incontestably right, as against the man who wrote the introduction. But let me make this request right away: Read as little as possible of literary criticism - such things are either partisan opinions, which have become petrified and meaningless, hardened and empty of life, or else they are just clever word-games, in which one view wins today, and tomorrow the opposite view. Works of art are of an infinite solitude, and no means of approach is so useless as criticism. Only love can touch and hold them and be fair to them. - Always trust yourself and your own feeling, as op-posed to argumentations, discussions, or introductions of that |

(continuation -from left frame - of Letter Three,

April 23, 1903) In this there is no measuring with time, a year doesn't matter, and ten years are nothing. Being an artist means: not numbering and counting, but ripening like a tree, which doesn't force its sap, and stands confidently in the storms of spring, not afraid that afterward summer may not come. It does come. But it comes only to those who are patient, who are there as if eternity lay before them, so unconcernedly silent and vast. I learn it every day of my life, learn it with pain I am grateful for: patience is everything!

But this power does not always seem completely straightforward and without pose. (But that is one of the most difficult tests for the creator: he must always remain unconscious, unaware of his best virtues, if he doesn't want to rob them of their candor and innocence!) And then, when, thundering through his being, it arrives at the sexual, it finds someone who is not quite so pure as it needs him to be. Instead of a completely ripe and pure world of sexuality, it finds a world that is not human enough, that is only male, is heat, thunder, and restlessness, and burdened with the old prejudice and arrogance with which the male has always disfigured and burdened love. Because he loves only as a male, and not as a human being, there is something narrow in his sexual feeling, something that seems wild, malicious, time-bound, uneternal, which diminishes his art and makes it ambiguous and doubtful. It is not immaculate, it is marked by time and by passion, and little of it will endure. (But most art is like that!) Even so, one can deeply enjoy what is great in it, only one must not get lost in it and become a hanger-on of Dehmel's world, which is so infinitely afraid, filled with adultery and confusion, and is far from the real fates, which make one suffer more than these time-bound afflictions do, but also give one more opportunity for greatness and more courage for eternity. Finally, as to my own books, I wish I could send you any of them that might give you pleasure. But I am very poor, and my books, as soon as they are published, no longer belong to me. I can't even afford them myself - and, as I would so often like to, give them to those who would be kind to them. So I am writing for you, on another slip of paper, the titles (and publishers) of my most recent books (the newest ones - all together I have published perhaps 12 or 13), and must leave it to you, dear Sir, to order one or two of them when you can. I am glad that my books will be in your good hands. With best wishes, Yours, Ranier Maria Rilke

My dear Mr. Kappus: I have left a letter from you unanswered for a long time; not because I had forgotten it - on the contrary: it is the kind that one reads again when one finds it among other letters, and I recognize you in it as if you were very near. It is your letter of May second, and I am sure you remember it. As I read it now, in the great silence of these distances, I am touched by your beautiful anxiety about life, even more than I was in Paris, where everything echoes and fades away differently because of the excessive noise that makes Things tremble. Here, where I am surrounded by an enormous landscape, which the winds move across as they come from the seas, here I feel that there is no one anywhere who can answer for you those questions and feelings which, in their depths, have a life of their own; for even the most articulate people are unable to help, since what words point to is so very delicate, is almost unsayable. But even so, I think that you will not have to remain without a solution if you trust in Things that are like the ones my eyes are now resting upon. If you trust in Nature, in the small Things that hardly anyone sees and that can so suddenly become huge, immeasurable; if you have this love for what is humble and try very simply, as someone who serves, to win the confidence of what seems poor: then everything will become easier for you, more coherent and somehow more reconciling, not in your conscious mind perhaps, which stays behind, astonished, but in your innermost awareness, awakeness, and knowledge. You are so young, so much before all beginning, and I would like to beg you, dear Sir, as well as I can, to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don't search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer. Perhaps you do carry within you the possibility of creating and forming, as an especially blessed and pure way of living; train your for that - but take whatever comes, with great trust, and as long as it comes out of your will, out of some need of your innermost self, then take it upon yourself, and don't hate anything. Sex is difficult; yes. But those tasks that have been entrusted to us are difficult; almost everything serious is difficult; and everything is serious. If you just recognize this and manage, out of yourself, out of your own talent and nature, out of your own experience and childhood and strength, to achieve a wholly individual relation to sex (one that is not influenced by convention and custom), then you will no longer have to be afraid of losing yourself and becoming unworthy of your dearest possession. Bodily delight is a sensory experience, not any different from pure looking or the feeling with which a beautiful fruit fills the tongue; it is a great, an infinite learning that is given to us, a knowledge of the world, the fullness and the splendor of all knowledge. And it is not our acceptance of it that is bad; what is bad is that most people misuse this learning and squander it and apply it as a stimulant on the tired places of their lives and as a distraction rather than as a way of gathering themselves for their highest moments. People have even made eating into something else: necessity on the one hand, excess on the other; have muddied the clarity of this need, and all the deep, simple needs in which life renews itself have become just as muddy. But the individual can make them clear for himself and live them clearly (not the individual who is dependent, but the solitary man). He can remember that all beauty in animals and plants is a silent, enduring form of love and yearning, and he can see the animal, as he sees plants, patiently and willingly uniting and multiplying and growing, not out of physical pleasure, not out of physical pain, but bowing to necessities that are greater than pleasure and pain, and more powerful than will and withstanding. If only human beings could more humbly receive this mystery - which the world is filled with, even in its smallest Things -, could bear it, endure it, more solemnly, feel how terribly heavy it is, instead of taking it lightly. If only they could be more reverent toward their own fruitfulness, which is essentially one, whether it is manifested as mental or physical; for mental creation too arises from the physical, is of one nature with it and only like a softer, more enraptured and more eternal repetition of bodily delight. "The thought of being a creator, of engendering, of shaping" is nothing without the continuous great confirmation and embodiment in the world, nothing without the thousandfold assent from Things and animals - and our enjoyment of it is so indescribably beautiful and rich only because it is full of inherited memories of the engendering and birthing of millions. In one creative thought a thousand forgotten nights of love come to life again and fill it with majesty and exaltation. And those who come together in the nights and are entwined in rocking delight perform a solemn task and gather sweetness, depth, and strength for the song of some future poets, who will appear in order to say ecstasies that are unsayable. And they call forth the future; and even if they have made a mistake and embrace blindly, the future comes anyway, a new human being arises, and on the foundation of the accident that seems to be accomplished here, there awakens the law by which a strong, determined seed forces its way through to the egg cell that openly advances to meet it. Don't be confused by surfaces; in the depths everything becomes law. And those who live the mystery falsely and badly (and they are very many) lose it only for themselves and nevertheless pass it on like a sealed letter, without knowing it. And don't be puzzled by how many names there are and how complex each life seems. Perhaps above them all there is a great motherhood, in the form of a communal yearning. The beauty of the girl, a being who (as you so beautifully say) "has not yet achieved anything," is motherhood that has a presentiment of itself and begins to prepare, becomes anxious, yearns. And the mother's beauty is motherhood that serves, and in the old woman there is a great remembering. And in the man too there is motherhood, it seems to me, physical and mental; his engendering is also a kind of birthing, and it is birthing when he creates out of his innermost fullness. And perhaps the sexes are more akin than people think, and the great renewal of the world will perhaps consist in one phenomenon: that man and woman, freed from all mistaken feelings and aversions, will seek each other not as opposites but as brother and sister, as neighbors, and will unite as human beings, in order to bear in common, simply, earnestly, and patiently, the heavy sex that has been laid upon them. But everything that may someday be possible for many people, the solitary man can now, already, prepare and build with his own hands, which make fewer mistakes. Therefore, dear Sir, love your solitude and try to sing out with the pain it causes you. for those who are near you are far away, you write, and this shows that the space around you is beginning to grow vast. And if what is near you is far away, then your vastness is already among the stars and is very great; be happy about your growth, in which of course you can't take anyone with you, and be gentle with those who stay behind; be confident and calm in front of them and don't torment them with your doubts and don't frighten them with your faith or joy, which they wouldn't be able to comprehend. Seek out some simple and true feeling of what you have in common with them, which doesn't necessarily have to alter when you yourself change again and again; when you see them, love life in a form that is not your own and be indulgent toward those who are growing old, who are afraid of the aloneness that you trust. Avoid providing material for the drama that is always stretched tight between parents and children; it uses up much of the children's strength and wastes the love of the elders, which acts and warms even if it doesn't comprehend. Don't ask for any advice from them and don't expect any understanding; but believe in a love that is being stored up for you like and inheritance, and have faith that in this love there is a strength and a blessing so large that you can travel as far as you wish without having to step outside it. It is good that you will soon be entering a profession that will make you independent and will put you completely on your own, in every sense. Wait patiently to see whether your innermost life feels hemmed in by the form this profession imposes. I myself consider it a very difficult and very exacting one, since it is burdened with enormous conventions and leaves very little room for a personal interpretation of its duties. but your solitude will be a support and a home for you, even in the midst of very unfamiliar circumstances, and from it you will find all your paths. All my good wishes are ready to accompany you, and my faith is with you. Yours, Rainer Maria Rilke |

|

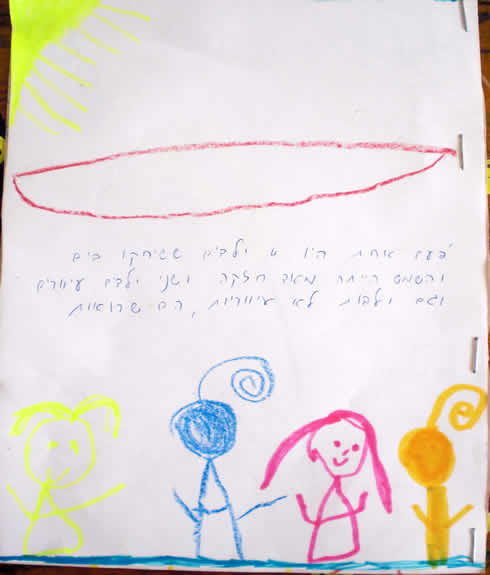

Mika in her own house

at Shoham, since June 28, 2010, "...Manifestation

is meant to be a playground

|

As I said - on August 5, 2010, I still stayed on, despite

Immanuel's return from flight ,

since in the evening the couple wanted to go out to a "chef-cooking"

with their friends at Re'ut

|

|

may be a faint reminder of the eating-drama , that goes on between mother and daughter day after day, meal after meal.....

|

|

I catch the pretty couple in the lift, - Immanuel

with the things he has prepared already beforehand.

While watching yet another program of "A Star is born", Mika plays with the ten-Sheqel coins, discerning the palm-tree on one side. |

|

The next morning, Aug. 6, Immanuel brought me - alreay

at 6 AM - to the hitchhike junction.

Unlike the next time - on Aug. 17, when I stood there , untaken, for 1 1/2

hours - the first car stopped.....

On Sunday, Aug. 8, I was already back at Shoham, 2 hours earlier than planned,

since Efrat wanted me to quickly write

the introduction for

Ayelet's, Mika's cousin's book.

We had planned it already in May, when I was perplexed what to give to Ayelet's

Bat-Mitzvah.

Efrat suggested that I gather photos of Ayelet on my computer, of which she

then would make a printed book.

I did the work right there and then, knowing, that later neither I nor Efrat

would have the time for it.

When I realized, that the amount of photos till Ayelet's fifth year was enough

to fill a book, I let go.

Remembering my experiences with all my grandchildren and "God's"

saying somewhere,

that after the age of five there is rarely a human being on this present planet

who truly lives,

I called the collection: "The Life

of Ayelet, which Ayelet knew NOT".

Ayelet, not yet four years old, with her cousin

Rotem, in June 2002

The hours with little Amit were exceptionally stressful for Efrat, and therefore for Mika (nevermind Grandma...)

|

|

|

|

But later at night, This was obviously her way |

On Monday, August 9, 2010, I was finally all alone with

Mika during Efrat's absence from 8:30 till 4 PM.

This has never happened since March

2007, when Efrat agreed to join Immanuel on a flight abroad.

And even then she did not trust me to manage alone, but asked Elah to help

me (thus making it less easy ...)

It is still enormously difficult for Efrat to let go of her obsession with

CONTROL,

especially concerning Mika's "eating-properly" and Mika's "enjoying-herself-without

boredom".

I've never seen Mika bored, and I was glad to have the chance to watch,

if this would be true also , when she would be alone with me for hours.

We did go to the pool, though .

|

|

|

Compare my hand holding the cellphone with Mika's

delicate hands |

I showed her the first photo, and she said: "it looks like The Tired Alon" (her brother...) |

|

She has made great progress, since I heard her last time, some months ago. "It is a sad song", she comments, obviously inspired by "Lament"... |

|

|

|

|

Mika's invention, immediately adopted by me: to eat the

wonderful soup with a straw!

But the rest of our meal was not so funny -

I had to find a way of neither betraying her mother's commands,

nor betraying my own beliefs

["you don't want to eat? Then don't. Wait

for the next meal-time! And of course, no sweets in between!

Also: do you know, that every

8 seconds a child in the world is dying of hunger? So why force you to

eat?"]

not to talk about my need to not waste our precious time

with nudging, coercing, bribing, threatening etc.

|

Continuation of Mika's

"Heaven-on-Earth" , in March 2010, on the

Song page of May 28, 2007 |